News

Update on Gall Bladder Mucocoeles

16th January 2019

By Daniella McCready, European Specialist In Small Animal Surgery

Gall bladder mucocoeles are probably one of the most common reasons for us to perform surgery on the extrahepatic biliary system. Management of gall bladder mucocoeles can be challenging as they can be easily missed but may also be an incidental finding. Hopefully this article will help you identify this disease more easily and assist you in the management of this condition.

What is a gall bladder mucocoele?

Cystic mucosal hyperplasia and hypersecretion of mucus leads to an accumulation of thick gelatinous bile within the gall bladder. Increased viscosity over a period of weeks/months leads to the filling of the entire gall bladder, and in some cases the hepatic and common bile ducts with mucus. The underlying cause is still unknown however genetic predispositions may play a role – Shetland Sheepdogs, Miniature Schnauzers, Cocker Spaniels, and more commonly Border Terriers, are known to be predisposed. Mucocoeles usually occur in older dogs. There is no sex predilection. In addition, mucocoeles have been linked to endocrine disease such as hyperadrenocortism and hypothyroidism. The presence of Cushings increases the risk of a gall bladder mucocoele by 29 times. Other factors that may play a role include dyslipidaemia, exogenous use of corticosteroids and dysmotility of the gall bladder.

Complications of a gall bladder mucocoele include extrahepatic biliary obstruction, cholecystitis and gall bladder rupture (in up to 60% of cases) leading to biliary peritonitis.

What are the clinical signs of a gall bladder mucocoele?

Clinical signs can be vague and non-specific. Signs that can occur include decreased appetite, lethargy, vomiting, abdominal pain and icterus.

How are gall bladder mucocoeles diagnosed?

Any evidence of hepatobiliary disease in dogs, esp. predisposed breeds, requires further investigations to rule out a gall bladder mucocoele. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical signs, physical examination, laboratory analysis as well as abdominal imaging.

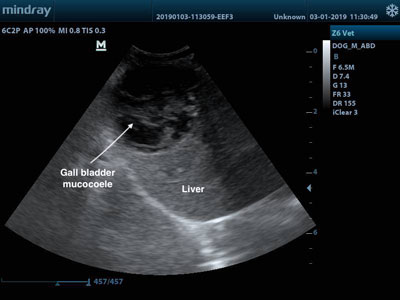

Physical examination may demonstrate cranial abdominal pain and icterus. Biochemistry will show an increase in ALT, ALKP, and total bilirubin (however this can be normal in early cases). In addition a leucocytosis can be present. Abdominal ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice. The classic ultrasonographic finding is of a stellate or finely striated pattern within the gall bladder. This is commonly referred to as a ‘kiwi fruit’ gall bladder. Biliary sludge can be confused for a gall bladder mucocoele however biliary sludge will move with gravity.

Kiwi fruit gall bladder

An important part of the ultrasonography examination is to rule out the presence of rupture of the gall bladder. The presence of free fluid in the abdomen, hyperechogenicity of the fat surrounding the gall bladder or discontinuity of the gall bladder wall are highly suggestive of rupture of the gall bladder and bile peritonitis. If free fluid is evident then an abdominocentesis would be indicated. Bile peritonitis would be confirmed if the bilirubin in the abdominal fluid is >2 times that of the peripheral blood. Cytology will demonstrate bile pigments. These cases are considered an emergency, and after appropriate stabilisation, an emergency exploratory celiotomy is required.

How do we treat gall bladder mucocoeles?

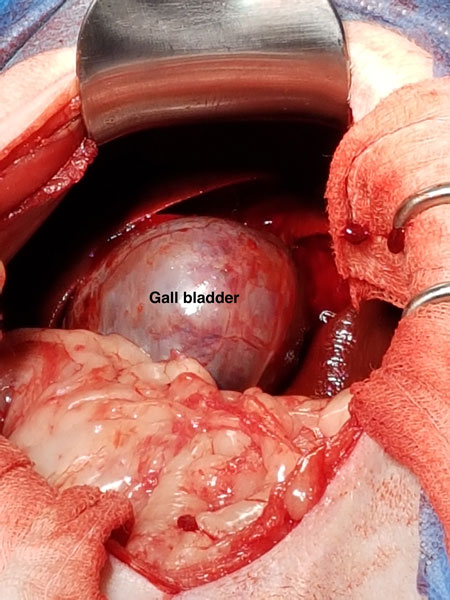

Whilst medical management of gall bladder mucocoeles, with S-adenosyl-L-methionine and famotidine, has been reported there is no significant literature supporting the use of medical management. Therefore, surgical removal of the gall bladder (cholecystectomy) is the treatment of choice. Whilst diversion of the biliary tract with a cholecystoduodenostomy has been reported, the gall bladder wall is often abnormal and progressive necrosis of the wall following surgery can occur leading to biliary peritonitis. In addition the continued production of mucus by the abnormal gall bladder wall would prevent resolution.

As for any hepatobiliary surgery a coagulation profile should be performed pre-operatively. If the coagulation tests are prolonged, then consider administering Vit K1 or fresh frozen plasma prior to surgery. A broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic should also be administered peri-operatively. It may be appropriate to obtain samples for bacterial culture prior to initiating peri-operative antibiosis.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed in selected cases. These include cases where there is no evidence of gall bladder rupture or extrahepatic biliary obstruction. However, the majority of cholecystectomies are performed with a standard open celiotomy.

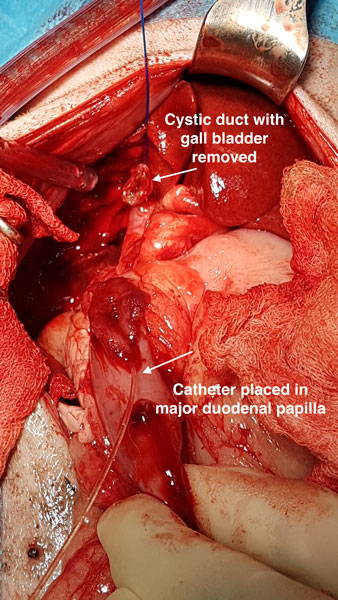

In 30% of cases of gall bladder mucocoeles, the common bile duct can be obstructed with congealed mucus. Prior to performing a cholecystectomy, the patency of the common bile duct needs to be assessed. Hyperbilirubinaemia and distension of the common bile duct on ultrasound may suggest partial or complete obstruction of the common bile duct. At the time of surgery, the common bile duct should be catheterised and flushed with saline via a duodenotomy (small incision on the anti-mesenteric side of the duodenum to visualise the major duodenal papilla). This is to establish patency as well as to remove any congealed mucus prior to removing the gall bladder. Retrograde catheterisation of the common bile duct with a 3-4FG feline urinary catheter via a duodenotomy is far simpler than normograde catheterisation.

The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of gall bladder mucocoeles is unclear – the reported rates of bacterial infection in association with gall bladder mucocoeles is 30-60%. Therefore, it is advisable to submit the gall bladder wall for bacterial culture and sensitivity, as well as histopathology. In addition, a hepatic biopsy should also be sent for histopathology.

If bile peritonitis is present the abdominal cavity should be copiously lavaged with warm sterile saline and all fluid suctioned. Primary closure of the abdominal cavity is usually indicated – a closed suction abdominal drain is rarely required as the source of contamination should have been resolved. Nutritional support with a feeding tube may be required in severe cases of bile peritonitis.

What is the prognosis following surgery for a gall bladder mucocoele?

The prognosis following a cholecystectomy for a gall bladder mucocoele is favourable and the majority of cases will return to normal. The prognosis is slightly worse if there is evidence of bile peritonitis, however with the correct management of these cases, the majority make a full recovery.

Complications that can occur following a cholecystectomy for a gall bladder mucocoele include biliary peritonitis, pancreatitis and re-obstruction of the common bile duct with congealed mucus/bile. The peri-operative mortality rate has been reported as 20% however in our experience this is much lower. The majority of dogs which survive the peri-operative period will have no long-term recurrence.

What to do with the incidental gall bladder mucocoele?

Deciding what to do with incidental gall bladder mucocoeles can be difficult. Firstly, is it a mucocoele? Don’t confuse an early mucocoele with gall bladder sludge. Sludge within the gall bladder is a common and completely incidental finding in dogs and is usually differentiated on abdominal ultrasound as mobile multiple echogenicities with the gall bladder. Secondly, there is debate as to whether incidental gall bladder mucocoeles exist. Often these cases, upon further investigation, show some mild clinical signs or laboratory abnormalities consistent with hepatobiliary disease. In addition, the concern regarding delaying surgical management in these cases is the risk of progression and therefore gall bladder rupture and secondary biliary peritonitis. In conclusion, unless there are specific contra-indications for surgery, the presence of a gall bladder mucocoele necessitates a cholecystectomy.

Back to news & events